About Deploying on Fridays

Common knowledge says that you don’t deploy on Friday if you want to have a peaceful weekend. Yet, some people will tell you that if you’re not comfortable deploying every day of the week, you’re doing it wrong. They’ll say that deploying shouldn’t be scary and that you probably don’t have enough tests. So, which one is it?

The problem with Fridays

Fridays are the last day of the working week, and for many teams, it might also be the end of the sprint/cycle/iteration. Explicit or not, there’s a deadline looming between the developer and the weekend. We invested long hours on this new feature, and we just want to push it out the door, close the ticket, and come back to a clean slate on Monday. Nobody likes heading into the weekend feeling like a fraud because they couldn’t complete the planned tasks in time. The bigger the task, the more eager we are to close it.

So what do we do? We rush it. Maybe we skip testing in a staging environment or turn a blind eye to that flaky test that always fails, and we ship it. We feel the weight being lifted off our shoulders as we click deploy, and we head out the door smiling, ready to enjoy the weekend.

Only somebody will have to clean up our mess when things go south.

When is a task completed?

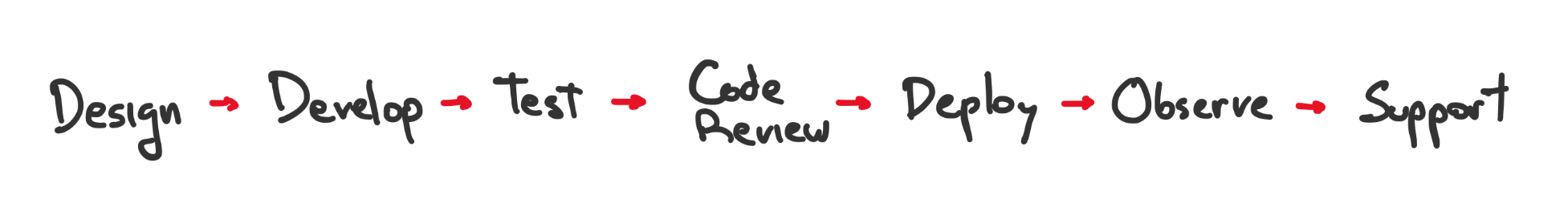

To understand how to combat the danger of Fridays, let’s consider the software lifecycle. That is, the things that happen between “I have to implement feature X” and “people using it in production”.

From the developer’s point of view, when would you say that feature X is Done? Is it once the branch is merged? Is it after the code is deployed? The answer depends on what your team considers the developer’s responsibility. On teams doing Full Cycle Development, the same person writing the code is the one that will test, operate and deploy the service. Which means that the feature can only be marked as Done once it’s being used in production.

Deploying is only one step, after which you release the change to some (or all) of your users and observe that it is working as intended. Spoiler Alert Sometimes it won’t be, and you’ll have to go back to the code and add little fixes here and there.

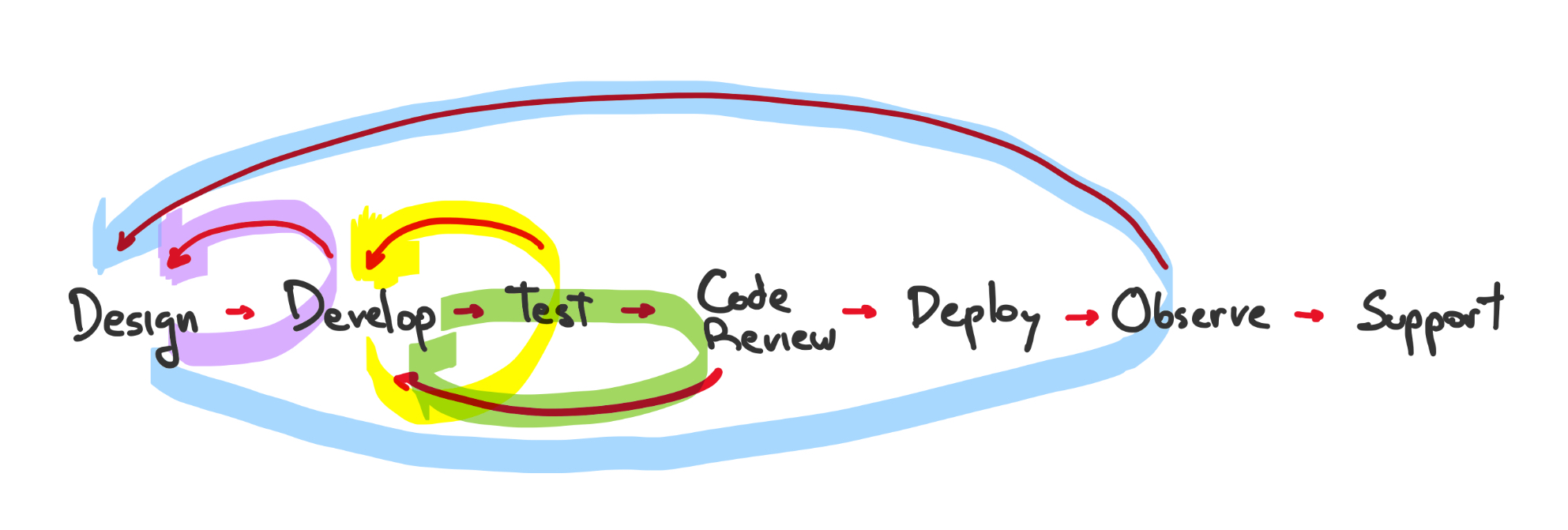

Treating deployments as just another phase of the software lifecycle enables Observability Driven Development. Letting developers see how their code behaves in production before closing the task.

Optimizing the feedback loops

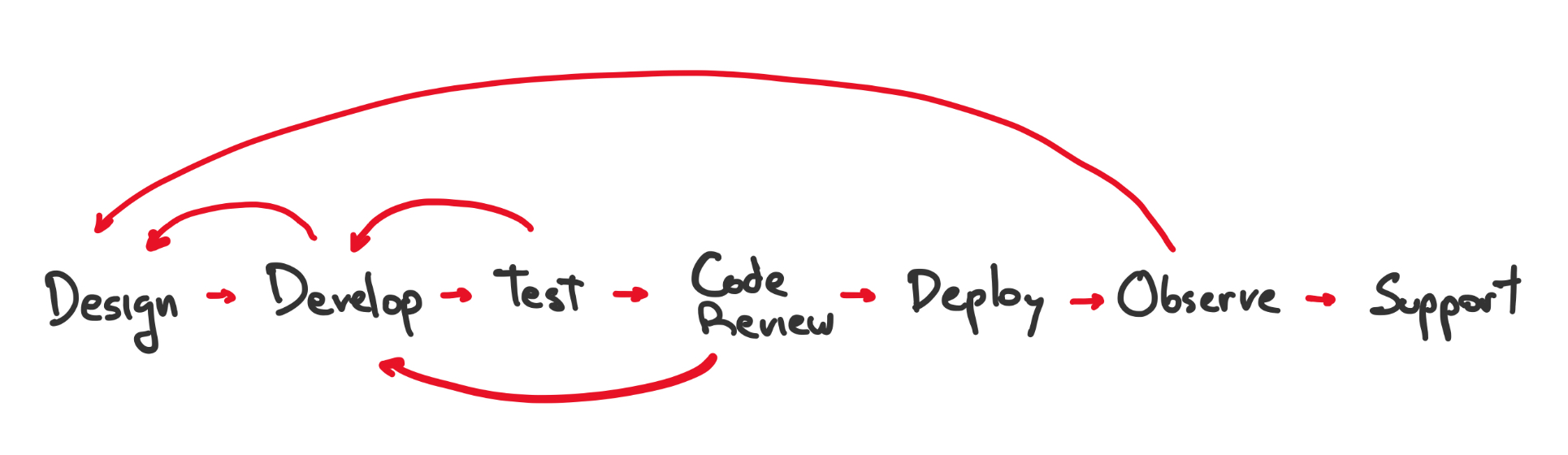

The software lifecycle diagram shown above is an over-simplification. In reality, the flow is never a straight line. Every step can send you back to a previous step: Started coding and found a flaw in the design, go back to design 🔙, a test started failing, go back to develop 🔙, etc.

The secret sauce to a highly efficient team is keeping these feedback loops as short as possible. If your tests take thirty minutes to run, by the time you see the failure, you’re already deep in some other task (or worse, on your 9th YouTube video).

Deploying is no different. If it takes months for your code to reach production, by the time your users start using your new feature (and uncovering bugs), you have already moved on to something else. You no longer have the context fresh on your mind, and you barely recall the details and the design decisions taken at the time (which is why you should be documenting those decisions).

How to make deployments less scary

The single most important change you can make to have less scary deployments, is to deploy small changes. Ideally, deploying one change at a time. One Pull Request ➡️ one Deploy. This will inevitably lead to more deployments because now you might have to do ten deployments to match your big dump releases of the past. This is good! The more you deploy, the less scary it is.

Deploying small changes also gives you better visibility into how your code is affecting the service. By releasing one change at a time, developers can use telemetry to observe how the code behaves in production and spot bugs before your users do. In contrast, if you batch multiple PRs in a single deploy, you might have a harder time figuring out which of the changes caused the issue. You might even have to convince the developer that what caused the issue is indeed their commit and not somebody else’s bundled together in the same release. You can avoid all this hassle by following the “one PR ➡️ one Deploy” rule.

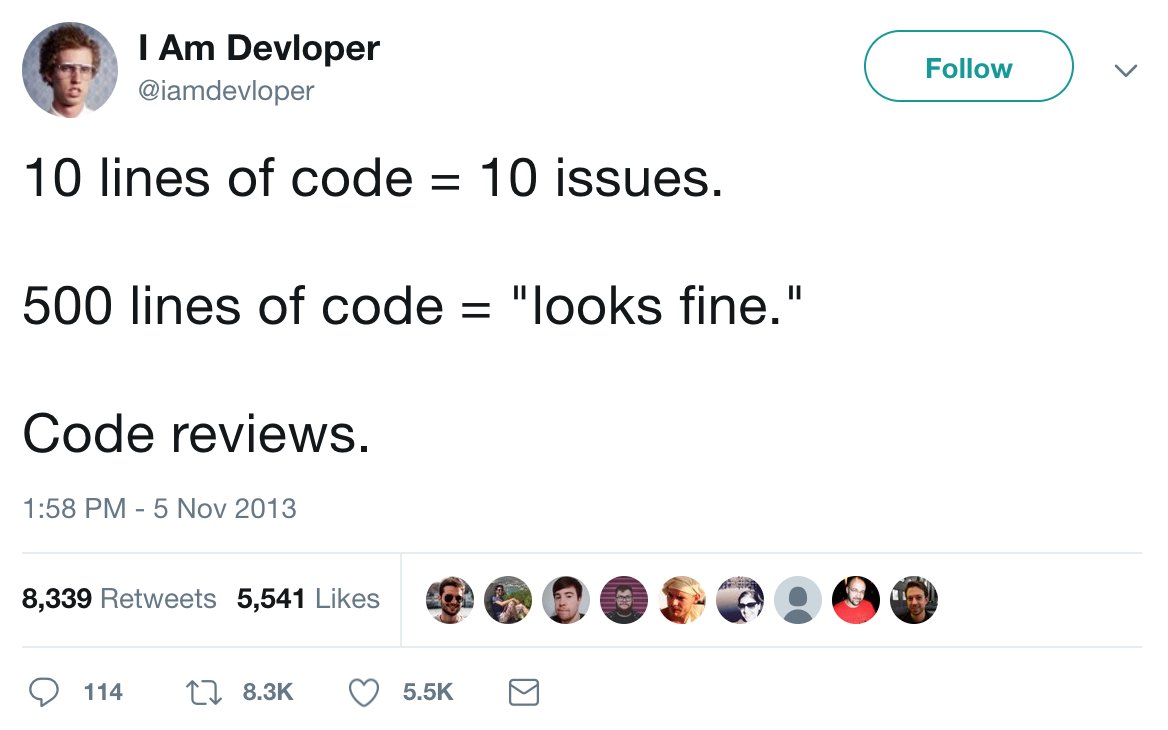

And the benefits don’t end there! Smaller changes also mean shorter code reviews. It’s easier for developers reviewing your code to spot bugs in a small PR than in a huge one that modifies hundreds of lines. This is another way in which smaller changes bring better code quality.

Last but not least, smaller PRs produce short-lived branches, reducing the number of merge conflicts one has to deal with.

Deploying != Releasing

For this approach to work, you need to trust devs with the keys to production. Depending on how your team operates, this might sound risky. Are you saying developers can put code in production whenever they want? Yes! That’s exactly what we’re advocating for. As pointed out earlier, this will mean more deploys, but it’s generally safer than the humongous release approach. Even if it feels like you lose control of what goes out the door. Yes, you’ll be deploying bugs from time to time, but the blast radius is limited, and the change is easier to rollback.

Now, this doesn’t mean that all users are immediately able to see the new changes as soon as you deploy. The terms deploy and release are sometimes used interchangeably, so let’s define how we’ll use them here:

- Deploy: Put a new version of the code in production.

- Release: Make some functionality available to users.

You can (and should) still control at what rate new functionality is released to users. You might use a rollout strategy where only a subset of power-users get to see what you’re working on and provide feedback before the feature is released to a broader audience. Or, you might want to start by observing how it works on a small percentage of users and then gradually roll out to everyone else. You can achieve this by hiding the new code behind Feature Flags and have it conditionally enabled. This provides the extra benefit of being able to enable and disable the code with a simple configuration change (without requiring a deploy), should a critical bug be found.

It’s not about testing

One common argument from the “deploy on Fridays” camp is about testing. It goes like this:

If you’re scared of deploying on a Friday, it means you either don’t have enough tests or your tests are not good enough.

I don’t buy it.

No matter how many tests you have, how good your coverage is, you can’t be sure you’re not releasing a bug. In the words of Dijkstra: Program testing can be used to show the presence of bugs, but never to show their absence.

Most automated tests are about validating the scenarios the dev can come up with during development. They don’t account for things we can’t predict1. So most testing is limited by the imagination of the person writing the test.

Furthermore, our tests usually run in a fake environment where many of the components are mocked. From service stubs to in-memory databases, we use every trick in the book to reduce non-determinism from our tests, but this comes at the cost of test fidelity. Our tests no longer accurately represent what happens in production. This is why we need observability and testing in production. This is why we need to deploy and observe to ensure our code is working as intended.

Conclusion

To sum up, deploying is just an additional step of the software lifecycle. You should deploy any day of the week, providing you’re willing to stick around to observe how your code behaves in production. If you just want to deploy, and run home to start the weekend, then maybe don’t. Because no matter how many tests you have, you haven’t seen your code running in a real environment yet. In the future, we might have DevOps AI to observe and rollback our changes automatically if something looks weird. Until then, though, you’re on the hook for making sure your code is working as intended. Especially on Fridays.

Piecemeal deployments will help you release faster and will improve your code quality. The idea is counter-intuitive, but it works: you have to do the scary thing over and over until it becomes an uninteresting event. Releasing frequently will help you catch bugs sooner and will make your team more efficient.

Many of the ideas in this post are inspired by the podcasts Oll1cast and Maintainable, as well as the books Software Engineering at Google and Distributed Tracing in Practice. If you enjoy these topics, go check them out.

-

That’s what exploratory testing is for, and it’s a creative endeavor that doesn’t scale linearly with code.↩