Go Channels in Kotlin - an Example

This is the story of a real use case that was solved by using Go style channels in Kotlin.

The use case

At work we have this CI/CD pipeline to get our code into production, and we needed a way of visualizing the Merge Requests that currently in the pipeline.

To make this happen we have 2 things:

- The GitLab service, accessible through REST

- The commit SHA of the last Merge Request that went into production

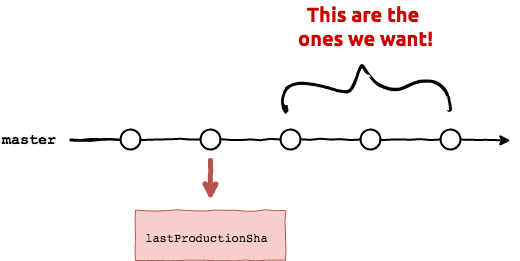

Now the problem is that Merge Request endpoint doesn’t allow for this kind of query. You can only search Merge Requests by title or description which is not what we want. So our only option is to get the latest Merge Requests up until we see the one that is in production.

The REST endpoint is paginated, and by default each response will contain 20 items. But what happens if the Merge Request we are looking for is not in those first 20 elements? We’ll need to keep making requests for new pages until we find the item we’re interested in. It’s not the most elegant solution but we’ll have to make do with what we have.

Our first approach: imperative

Our first try of putting that last paragraph into code looked something like this:

Not pretty, but it does the job.

The next attempt we made was implementing it as an Iterable. And it was even uglier! Believe me, you don’t even want to see that one. Your retina might burn just from looking at the code…

Using buildSequence

We kept looking for a way of making the code cleaner, so we decide to try using buildSequence. It seemed like a good idea because a sequence can be thought as an Iterator where the values are evaluated lazily. So potentially Sequences can be infinite.

To make use of this feature we needed to add the kotlinx-coroutines-core to our project. Anyway, this is how the code looked like:

Let’s unpack it:

- First we have the sequence declaration. We call the build sequence function which receives a lambda with receiver:

SequenceBuilder<T>.() -> Unit. This allows us to call the methodsyieldandyieldAllonce we have calculated the values to be produced on this sequence. We useyieldAllin this case because we receive a Collection of values from the REST call, otherwise the type of the sequence would be:Sequence<List<MergeReques>>whereas we only needSequence<MergeRequest> - We use

takeWhile { ... }to only get the Merge Requests that are not in production. - We convert the sequence to a List and return

You might be thinking ”Ok but, why is this better than the imperative approach?”

For starters this code is easier to read. This alone is reason enough in my book, as the quote goes:

”Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand.”

Martin Fowler

As a bonus by using a Sequence we get some extra flexibility. In the imperative approach the condition is right in the middle of the function. Using sequences we could easily have a function that generates the sequence and then write other functions that use it, leveraging all the awesome collection functions (filter, find, take, drop, etc).

It is important to note that when using sequences the evaluation is lazy (just like Java streams). In our case that means that takeWhile will only start once we call the toList function, because toList is a terminal operation.

So are we using coroutines now? YES! But… buildSequence is coroutine builder that creates a synchronous coroutine. This means that even thought it uses coroutines everything is executed sequentially.

Using channels

Finally we decided to go all in on coroutines by using channels. This is the result:

Now we have a function that creates a channel, and we are using consumeEach to receive each of the elements the channel sends. Since consumeEach is a suspending function we have to call it from a coroutine context, runBlocking helps us bridge the gap between blocking execution and the coroutines world.

With ReceiveChannel we have the flexibility of Sequences, but we also get one more thing: concurrency!. You can see that I’ve added an artificial delay call before beginning to consume the Merge Requests. This is to show that even before the receiver is ready to consume the channel, the producer has already started to fetch elements. In this case since we’re using an unbuffered channel only one send will be called before suspending the coroutine. But that’s all we need since in our case sending 1 element means that we’ve already fetched the whole first page!