Pulling an Inverse Conway Maneuver at Netflix

When I first joined the Netflix Platform team circa 2020, the Observability offering was composed of a series of tools serving different purposes. There was Atlas for metrics, Edgar for distributed tracing, Radar for Logs and Alerts, Lumen for dashboards, Telltale for app health, etc. It was a portfolio of about 20 different apps. Big and small, ranging from business-specific tools to analyze playback sessions to low-level tools for CPU profiling.

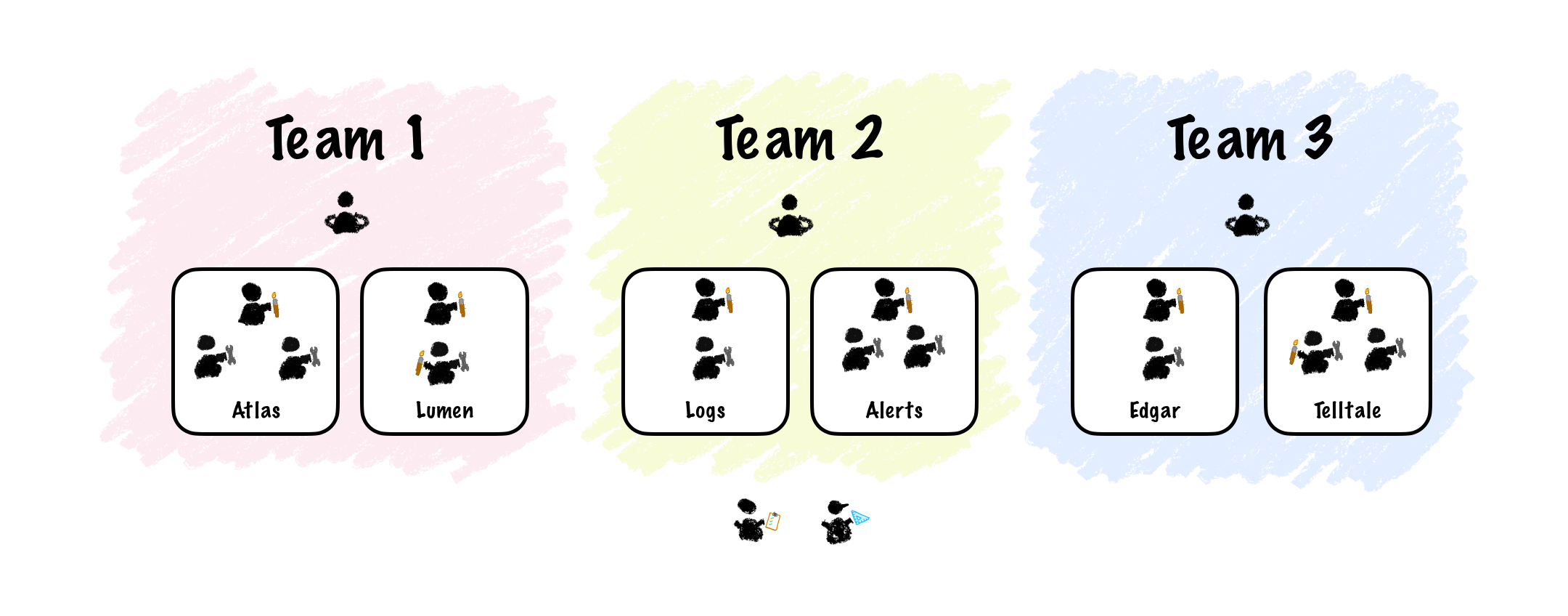

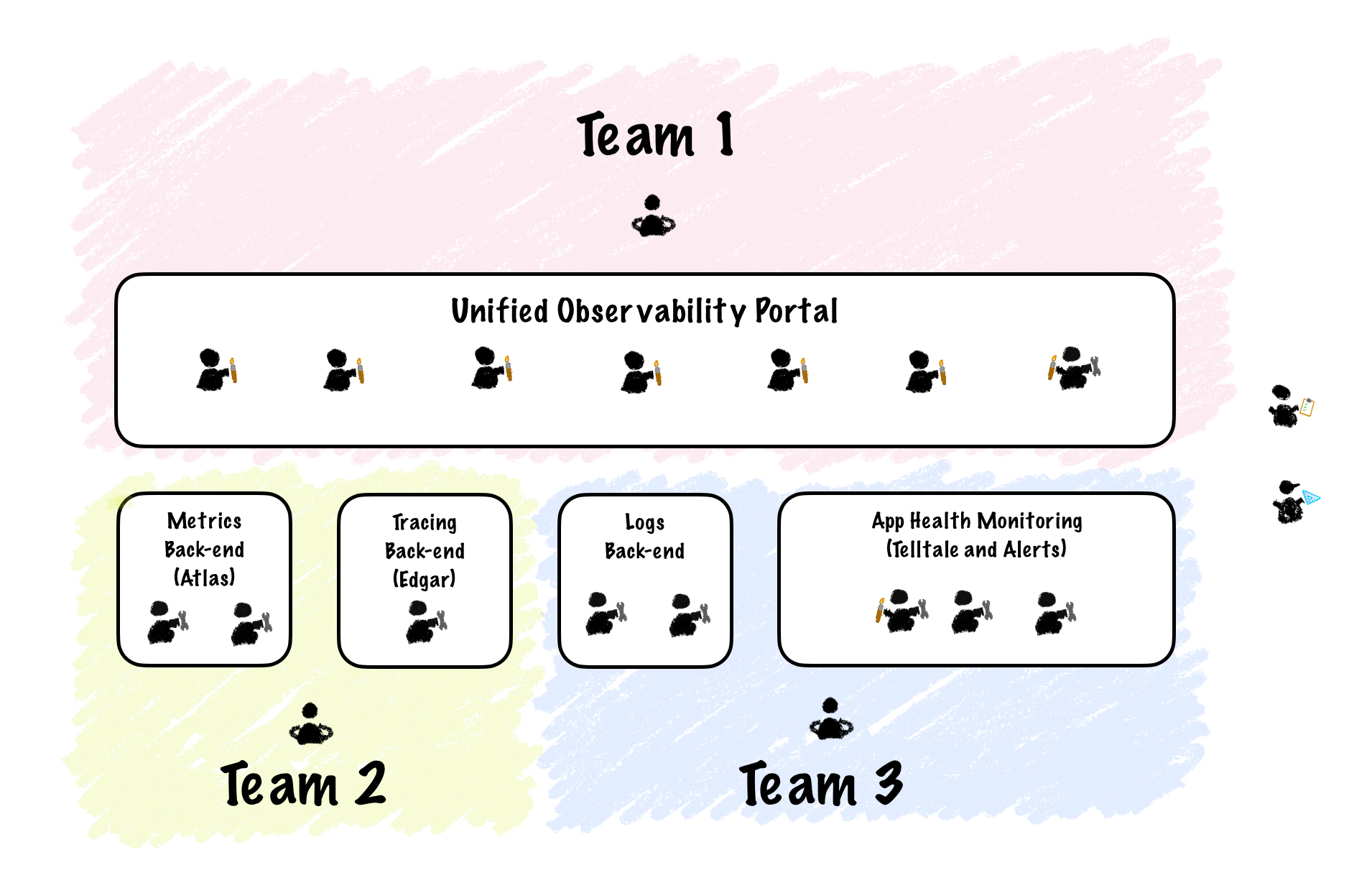

The Observability org was composed of three different teams. Each team had a mix of front-end, back-end and full-stack engineers. We also had one designer and one PM shared across the three teams. Each team was further subdivided into sub-teams of two to four engineers working on a specific sub-domain.

It was no coincidence that this org structure produced a set of independent apps. That’s the kind of architecture we’d expect based on Conway’s Law:

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

Melvin E. Conway

Simply put, the system’s architecture will be shaped like the org that produced it. This is because, to build a complex system, people must communicate to ensure the different pieces fit well together. Therefore, the design that emerges will be a map of the communications paths in the organization.

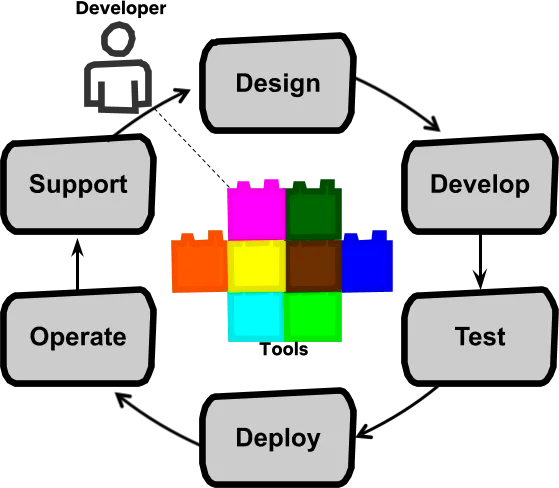

Netflix’s approach to building software further intensified this. Netflix embraces the Full Cycle Development; this means teams are fully responsible for all the stages of the software lifecycle, from Design to Operate and Support.

We were organized as highly aligned, loosely coupled teams with a high level of independence. ICs wholly owned every aspect of their work, from tech stack choices to which ticketing platform to use to track bugs. Netflix provides a recommended set of tools (known as “paved path”) but doesn’t mandate their adoption. Each team is free to pick whatever tools and practices suit them best.

Netflix has a “paved road” set of tools and practices that are formally supported by centralized teams. We don’t mandate adoption of those paved roads but encourage adoption by ensuring that development and operations using those technologies is a far better experience than not using them.

Extract from Full Cycle Development blog post

This produced a set of heterogeneous apps to serve the observability needs of the company. Each team would focus on its own sub-domain and individual products to deliver the best possible experience. And users were happy with the result. At least for a while…

By 2020, we started hearing a new kind of complaint. Users were beginning to get frustrated with the disjointed experience we provided for troubleshooting. Debugging a particular issue required them to replicate the same query across multiple tools and jump between tabs to assemble the pieces. To troubleshoot effectively, users had to be proficient with each tool and know when to use one or the other. To make matters worse, the different apps' documentation was scattered across multiple wikis, and we hadn’t done a great job teaching users about new tools and features. It also didn’t help that each app implemented its own base components (such as date pickers or query builders) with subtle variations. The required functionality was there, but it was only accessible to power users, and even then, having a comprehensive view of an issue took quite a bit of effort.

Our knee-jerk reaction to the feedback was adding deep links across apps so that users could jump to a different tool, taking the query context with them. This would make it easier to flow from one tool to the next when required. To make this happen, we had to start talking across the teams to align on a standard to send and receive contextual information through the links. Even something as trivial as this took us multiple meetings to agree on a standard that’d satisfy the needs of all apps of the portfolio.

Soon, we realized links were not going to cut it. We were also getting frustrated with how long it took us to coordinate these changes across teams. The links made the fact that we had some overlap between tools quite obvious. For example, you could pull all log messages for a given request in Edgar, but you’d see them on Edgar’s own log viewer component, which wasn’t as powerful at Radar’s. With deep linking, users could click the log message and see it on Radar, but at the cost of losing the request context, which only made sense on Edgar.

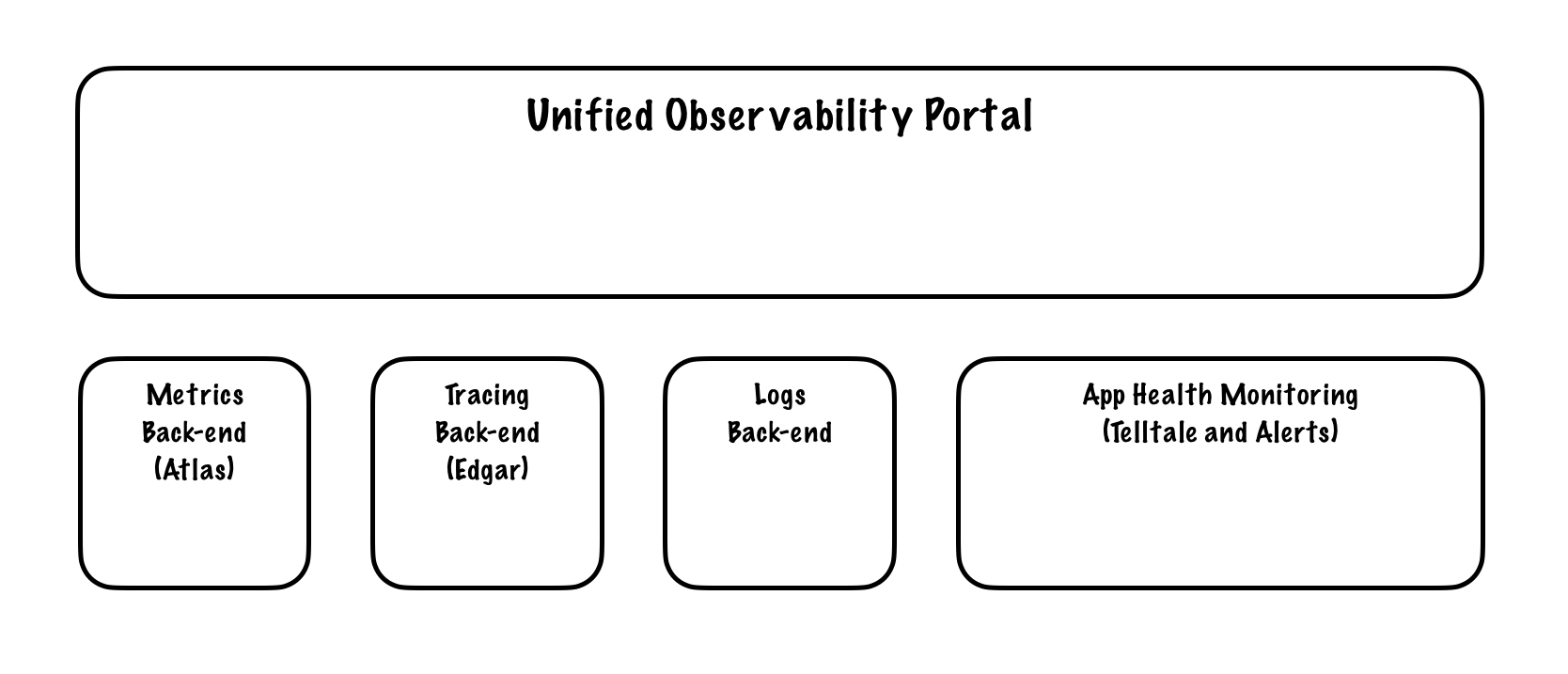

We came to the realization that if we wanted to provide a cohesive observability story we’d need a single application that lets users interrogate multiple data sets at once. A place where they could observe their systems from different angles without having to jump through various hoops.

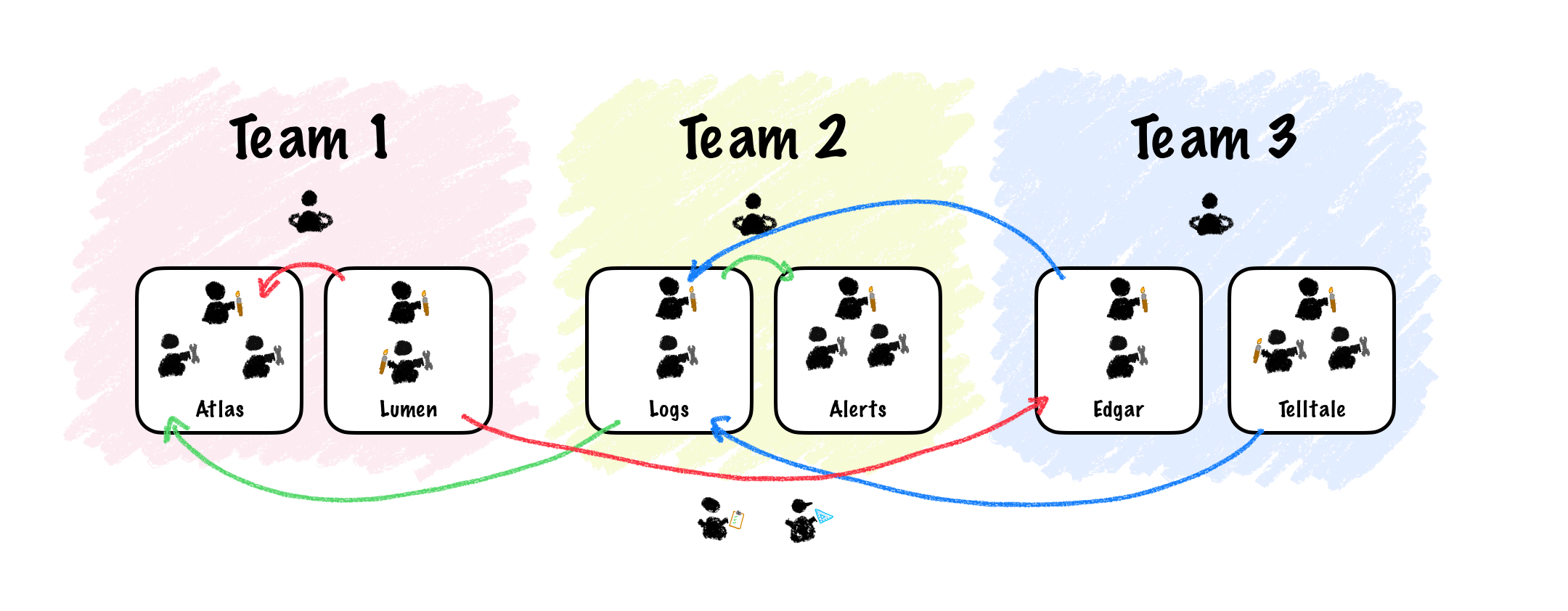

We knew what kind of architecture we were going for, and based on Conway’s Law we knew it would be hard to achieve it with the current org structure. So before we even discussed how we would implement anything, before we even knew if we were creating a new tool, a whole platform, or buying some ready-made solution, management made one decision. They pulled an Inverse Conway Maneuver and re-orged the teams. They re-shape the org structure to match the design solution we were going for, creating the communication paths required (and severing the ones not needed) to facilitate the work. And that is how the Explore team was born.

With this new structure, communication was optimized to produce a unified experience that’d include all existing features across logs, metrics, traces, alerts, and dashboards. The trade-off was that now the back-end for any given vertical lived on a different team. This implies less communication between front-end and back-end engineers, making working on features requiring alignment between both parts slower. Management considered before doing the re-org, and decided the cost was acceptable because the goal of unification was a higher priority on our roadmap.

The takeaways here are:

- The org structure limits the design solutions an org can produce for a given system’s architecture. This is Conway’s Law.

- If you know which architecture you aim for, you can adapt the org structure to facilitate arriving at your goal. This is known as the Inverse Conway Maneuver.

- You might need different org configurations during the lifetime of a system, depending on what your goals are at the time.

- It’s important to consider the trade-offs of choosing any given org structure, understanding which communication paths are being optimized and which ones de-prioritized, and how that affects the flow of work.

If you find this topic interesting, check out the book Team Topologies by Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais.